In November 2013, the African Development Bank approved funding for the construction of the Inga III Dam (or the Grand Inga), the first phase of the Inga, a much larger energy complex. The Grand Inga, stretching from South Africa to Egypt, thanks to its 39,000 megawatts produced, would provide a permanent supply of electricity for no fewer than 15 countries on the continent.

It is important to examine, through the example of the Inga dam, the ability of African states to carry out their objective of reducing their dependence on external aid in order to regain self-sufficiency in energy.

An Ambitious Project

Initially planned in 1982 by former Congolese leader Mobutu Seseko to supplant the shortcomings of the Inga 1 and 2 dams built during the 1960s, this project never materialised whilst he was in power, with political and security disturbances (civil wars, conflicts at the borders with Rwanda, exactions in North Kivu) having overcome the political fragility of this country.

More than three decades after this abandonment, the Congolese and South African heads of state began new talks to launch this ambitious project once more. Faced with the saturation of technical equipment and components of Inga 1 and 2, the explosion of energy demand in a regional sphere where 60% of inhabitants live without electricity, the renewal of national powering network was a matter of economic urgency and of vital importance. According to Jim Yong Kim, the World Bank Chief Executive, these facilities could solve the “energy apartheid” that the region has been experiencing for several decades.

1.5mis the number of jobs that the Grand Inga project could create

The economic benefits of the Grand Inga are not negligible for the states concerned. Although the spin-offs in terms of job creation are difficult to foresee for this single project, McKinsey estimated in a recent study that it would mean 1.5 million jobs created over the next few years. There is no doubt that a large portion of the workforce will be mobilised in the construction of Inga.

Hydroelectric power is a boon for governments. Due to a much lower consumption cost involved than with hydrocarbons (coal, uranium and petroleum), the extreme volatility of price in recent years, prompting most governments to diversify their operating resources. For example, the cost per kilowatt hour for the Inga project, estimated at $25, is twice as cheap as gas today (at between $47 and $67) despite subsidies from ECOWAS for industrialists in the sector.

On the other hand, the exorbitant cost of such a construction can be largely offset by the realisation of economies of scale – much more frequent with large electrical infrastructures than with small ones. This applies particularly to the Democratic Republic of Congo, which holds 50% of the total production potential of the African continent. The country could benefit from a favourable geographical setting in which the Congo River, the second longest river in Africa, is an undeniable asset. Under these conditions, the unit cost of production per kilowatt-hour would fall sharply because of the volume of water needed to deliver the expected yields.

Some Major Obstacles

The first visible obstacle concerns the financing of the project. Its total cost, estimated at €72bn, is higher than the GDP of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which reached only €39bn in 2015. The difficulty that the government of Joseph Kabila has in honouring its debts in the exploitation of Inga 1 and 2 only amplifies the reluctance of institutional and private donors to finance the Grand Inga. To reassure them, the Congolese authorities undertook to leave the management of the dam to a private entity.

The National Electricity Company (SNEL), a national operator with a monopoly on the distribution and transmission of electricity, is struggling to fulfil its mission to cover the national grid due to a lack of resources. This example demonstrates once again the burden borne by the corruption and incompetence of the leaders of major groups in the mismanagement of services of general interest.

One of the major shortcomings of the Grand Inga is the ecological issues involved. Many NGOs have criticised the World Bank for its lack of rigour in assessing the risks the project poses to the region. The construction of electric dams, involving the redevelopment of land surfaces on the shores of river coasts, is one of the main factors in the disappearance of marine species (fish, plankton, and so on) and terrestrial mammals.

Dams Vs Ecosystems

By 2014, the World Bank estimated that more than 6,300 people were displaced as a result of the destruction of homes. Inga III would run the risk of an over-monopolization of the Congo River by these infrastructures, which would affect the daily lives of the rural populations living in the surrounding areas as well at the level of the valley of the Bundi River Of these river areas. These communities, mainly from the fisheries and aquaculture trade, would see a large portion of their agricultural land devastated by the soil erosion caused by the dam.

According to Peter Bosshard, Director of International Rivers:

“The construction of hydroelectric power plants is incompatible with safeguarding the ecosystem of Great Lakes Africa due to the excessive amount of aquatic resources needed for their operation.”

However, the conclusions of the American NGO, which recommends a massive investment in the development of renewable energies (solar and wind) and the construction of smaller hydropower plants, are puzzling. Guaranteeing the distribution of electricity to the greatest number of people by extending the networks necessarily means an impact on the ecosystem of the region.

In addition, solar and wind energy have extremely limited production capacities compared to those displayed by gas and coal-fired hydroelectric plants. The installation of thousands of solar panels or wind turbines, in addition to increasing the spatial saturation of the territory, would not be enough to fill the energy deficit of this zone.

According to the World Bank projections, by 2040 only 6% of total electricity production in sub-Saharan Africa will be directly realised from the exploitation of these green hydroelectric sources, with 27% through coal-burning.

The Shortcomings of Regional Powers

Beyond the structural economic weaknesses of the African continent, Grand Inga demonstrates once again how much the continental states remain dependent on external financial, technical and material aid for the realisation of their ambitions.

The absence of a national company capable of supplanting the French EDF and American firm AECOM in the feasibility study phase of the project testifies to the difficulty of some African countries in dealing with the large mastodons of the energy industry – despite the vast potential of these territories.

After the first call for tenders launched in 2015, no African firm was among the consortia shortlisted to carry out the work. Thus China’s Three Gorges, South Korea’s Posco, and Spain’s ACS and Eurofinsa are currently the only serious contenders.

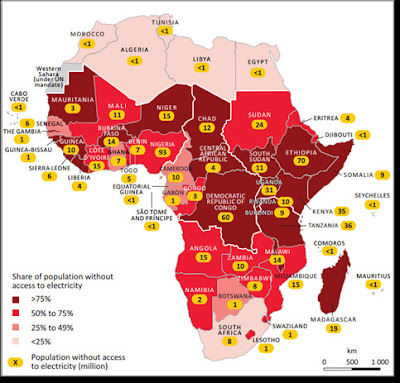

620m is the number of electricity-deprived Sub-Saharan Africans

Sub-Saharan Africa is a typical case of the low impact of macroeconomic policies on the daily life of local communities. Today, no less than 620 million inhabitants (or 48% of the population) are deprived of electricity in this region.

While the Congolese government has the ambition to surpass the 60% of the population with access to electricity by 2025, many analysts remain sceptical of the government’s ability to improve people’s daily lives. Indeed, even in areas where access to electricity is relatively developed, energy consumption rates remain very low compared to those in emerging countries (due to a low per capita GDP).

This raises the question of the conflicting interests and contradictions to which certain states, including the DRC, are confronted in their quest to increase their international influence. Indeed, it is ironic that Inga III, whose purpose is the supply of electricity to a quarter of the continent, is not in a position to mitigate the microeconomic failures observed in the Congolese energy market.

This problem only masks several others, including the sharing of material wealth and added value between the different components of Congolese society.

The Low Purchasing Power

There are many indications that the Congolese government will prefer – as with most of its projects for the construction of energy installations previously launched – strictly industrial exploitation of these energy pools, to the detriment of the needs of citizens. The deplorable state of communication networks and the isolation of the rural populations and of certain provinces such as the Kasaï-Oriental (in the centre of the DRC) leads us to question the effectiveness of such a strategy.

Apart from the fact that the lack of technical and material resources of the regional powers considerably slows down the progress of this major project, private investors remain sceptical about its potential profitability. The low purchasing power of Congolese, Zambians and Angolans reinforces the private sector’s doubts about the ability of these populations to achieve a high level of consumption at average prices.

The imbalances and irregularities observed in the energy consumption market can also be explained by the particular demographic structure of these countries, some of which have not yet completed their urban transition.

The power requirements of rural populations, which are sometimes difficult to estimate, pose many logistical problems for the provincial administrative authorities. Due to the complexity of the road tracing process and the transmission of electricity to remote rural areas, it is very likely that the price per kilowatt hour will be increased.

Regional Cooperation Questioned

While, for a long time, regional economic cooperation has been favoured for international influence and as a diplomatic instrument facilitating access to prosperity, it is clear that this model has been running out of fashion in recent years. Given the complexity of certain projects such as the Grand Inga, which require significant logistical means in terms of imports and the transport of people and materials, African states are often forced to favor the financing of their projects through institutional donors, mostly non-African, and thus yielding to their demands to the detriment of the interests of the local populations.

Free trade agreements promoted by interstate structures prove ineffective because of African leaders’ low propensity to implement international agreements at the national level. The economic crisis of 2008, having significantly affected the performance of national export economies, has only slowed down the process of creating unique markets.

Faced with the sometimes inconclusive results of measures to deregulate and harmonise commercial and legal standards, some leaders resume the use of unilateral policies, resulting in the maintenance or re-establishment of non-tariff barriers (subsidies paid to private companies, binding legal norms for African investors). For example, the bilateral agreements with China proved to be more fruitful and less binding, as evidenced by the 2015 partnership between South Africa and China which included the construction of a nuclear power plant.

In the electricity generation market, the regional integration of African countries has led, since the 1990s, to the creation of regional power pools, bringing together the main electricity companies with each of the states’ members of the intergovernmental organisation in question. For example, the Southern African Power Pool (SAPP) was established in 1995 under the leadership of the Southern African Development Community (SADC).

The objective of forming a new energy competitiveness cluster has not yet been achieved due to a lack of public investment in scientific research and the purchase of materials. The budgets allocated to the SADC remain insufficient to claim a geographical extension of the era of activity of the electric companies.

Conclusion

It is in the summer of 2017 that the Congolese State will designate the great winner of the call for tenders for the construction of Inga III. Whatever its identity, it will have the heavy task of including a whole continent within a project that mobilises a number of economic and political actors, among which states and regional integration organisations remain in spite of the difficulties faced.